|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2 October 2022 - a break from translation technology to talk about translation and time |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2 December 2021 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

13 October 2021 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Classics never go out of style |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recently reading a book on data visualization (watch this space for future visualizations of my data!), I noticed that the author said that there were three principles that should be followed. Data visualization should be trustworthy, accessible, and elegant (Kirk 2019, 38). Especially since the last principle was ‘elegance’, my mind jumped to Yan Fu’s three principles of translation xin, da, ya (信,達,雅). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Xin is often translated as “faithfulness” or “fidelity”, and certainly any claim to be faithful also involves being trustworthy. Da is a bit trickier, as it is usually a verb; “to reach (a goal)”, “to arrive (at a destination)”, hence to get across or to express your meaning; the idea that you manage to get something across, something gets from point A to point B; in order to get across the meaning, it must be accessible. Finally ya is almost always translated as “elegant”, exactly the term that Kirk uses in his book. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

is this just a happy coincidence? Or, if the principles are the same, are the processes somehow the same? In other words, should we be thinking of data visualization as a form of translation, one in which numbers in the form of spreadsheets are translated into a visual medium? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This has intriguing ramifications for the translation process. So often, we speak of what is lost in translation from one language to another. Yet the dominant trope in data visualization is one of gain through the translation of often difficult-to-read spreadsheets into clean, crisp visualizations that often reveal hidden patterns and therefore represent either new information. Or rather, we should speak of a new interpretation of the data – because the data was there all along, we just couldn’t see a particular pattern in grid form. When data scientists do speak of loss, they do so cheerfully: it is often not possible to ‘see’ every data point in a visualization, but that is actually a good thing, because by suppressing some detail, patterns become clearer. In other words, the overall message becomes clearer – or at least, the message that the visualizer wants to convey becomes clearer. For it also transpires that, like linguistic translation, visualization by different visualizers may yield different results, as different designers use different visualization tools to tell different stories. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This idea that visualization is interpretation leads us to another ‘classic’ in translation studies, George Steiner’s After Babel. But perhaps that’ s a story for another day. . . . |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Meanwhile, Yan Fu’s ideas seem to be holding up well in the twenty-first century! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

works cited: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Kirk, Andy. 2019. Data Visualisation: A Handbook for Data Driven Design. 2nd Edition. London: Sage Publishing. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Steiner, George. 1975. After Babel: Aspects of Language and Translation. London: Oxford University Press. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

20 October 2020 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Using online collocation tools for translator training |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

One course that I always enjoy teaching is our MA “Workshop”, for which each student chooses their own translation project. While the majority choose literary texts, a surprising number choose non-fiction, including scientific or technical texts, and so there is a real mix of text varieties and, therefore, translation challenges. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Since it is project-driven, the lectures, such as they are, must focus on topics that will be of use to most or all of the students, regardless of what sort of text they have chosen. One topic I have found quite rewarding to teach is the use of general English-language corpora for collocation studies. Since my students are not native speakers of English, collocation is one of the more serious obstacles they face when translating into that language. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Brigham Young University’s initiative, English-Corpora.org, is by far my favorite online site for such work. It contains seventeen different corpora, for a total of approximately 34 billion words. Of the various corpora, the ones I use most frequently are EEBO (see my earlier blog on this fantastic resource), The British National Corpus (BNC), and the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA). The last two especially are wonderful reference corpora consisting of a sampling of many different types of texts over a period of time; BNC covers the 1980s and early 1990s, while COCA covers 1990 through the present, with material added each year. Depending on whether my students are aiming to publish their work in the British or North American, I steer them toward one or the other. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

To take one simple example I used last year: the essay collection 十個詞彙裡的中國 by 余華, translated into English by Allan Barr as China in Ten Words, contains ten essays by the writer Hua Yu, each revolving around a single concept. One of the essays is entitled 山寨 (pronounced shanzhai), which Barr has translated as “copycat”. Shanzhai is a term that emerged first in the field of mobile phones and refers to imitation or knockoff versions; since then it has spread to mean almost anything inauthentic. Yet the literal meaning of the term is something like “mountain fortress”, and the implication is that the companies that produce such knockoffs (or copycat versions) are a bit like Robin Hood figures or local bandits, depending on your point of view: they are holed up in their mountain retreats, undermining central authority, thumbing their noses at the big guys. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

“Copycat” as a translation for this concept had bothered me when I first read Barr’s version, although I couldn’t put my finger on why the word seemed to be wrong. It turns out that it is an excellent example of how a collocation tool linked to a large corpus can give good reasons to re-consider word choice. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

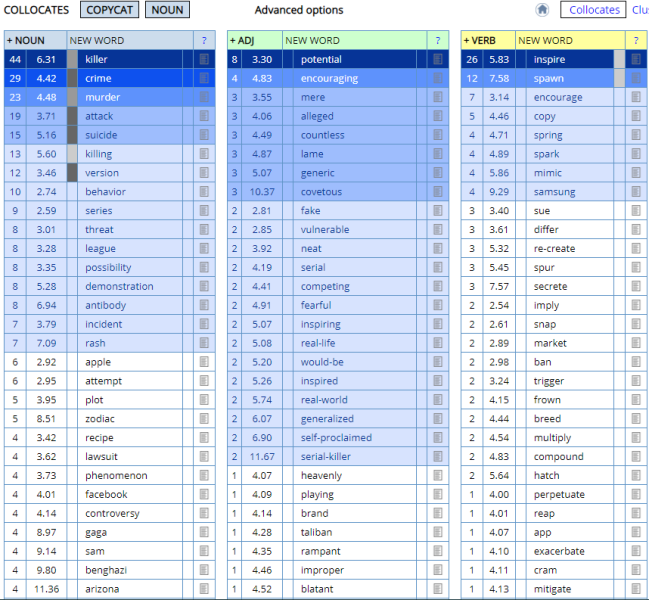

If we search for collocates for “copycat” in COCA, we get the following results: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

(In the interest of readability, I have excluded adverbs, which form a fourth column but have very low frequency: “emotionally” occurs twice and then all others are single results.) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

It is clear from the collocate list, dominated by nouns, that the top six results “killer, crime, murder, attack, suicide, killing” indicate that the word copycat in English is now firmly associated with not just crime, but violent crimes. This does not fit well at all with the meaning of shanzhai in Chinese and so, even though “copycat” can indeed mean imitation, I would argue that the “pull” of these collocations on the meaning of the term undermines it as a good translation. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Another example, taken from mistakes found in student translations, is the use of the verb “to play” indiscriminately with all sports. This is most likely due to the fact that in Chinese, you can “玩” (wan “play”) virtually any sport. In English, however, there is a range of sports that cannot take this verb: cycling, kayaking, windsurfing, fishing, et cetera (presumably because they are nouns formed from verbs, and so English continues to use the verbs “kayak, windsurf, fish”, et cetera). Either COCA or the BNC will immediately identify this problem; if you search for collocates of these sports in COCA, you will not find “play” anywhere in the list. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I also demonstrate to students the difference between strong and weak collocations, again based on an example drawn from a student, who used the term “elderly” with “geezer”. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

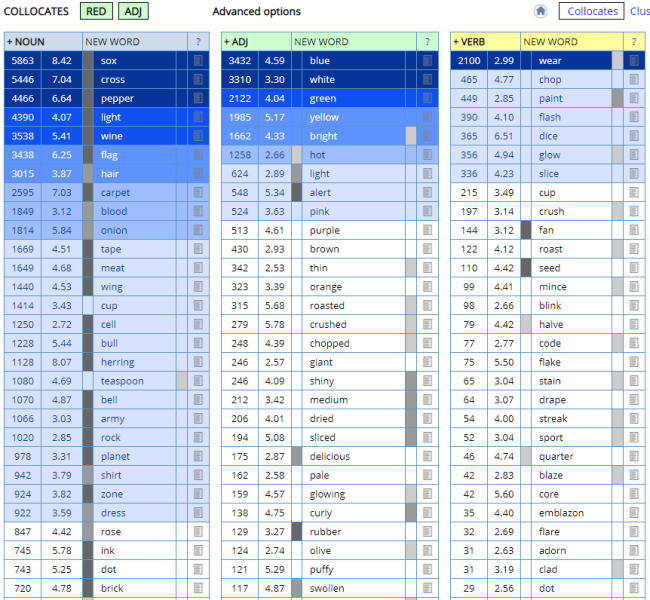

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

COCA shows no occurrences for “elderly” as a collocate with geezer; but more to the point, there is one single word, “old”, that has 224 hits, while the next most common term after that is “greedy” with only 15 hits, or approximately 6% of those for “old”. We can compare this situation, where “geezer” collocates overwhelmingly with one term and then weakly with all terms, with a term like “red”, where the top collocate “Sox” (I’m from Boston, so have chosen this example deliberately to shout out to the local baseball team the Red Sox!) has 5863 hits. 6% of 5863 is 351; there are fifty terms that are at or above that 6% threshold, and the one nearest to Sox, “cross”, has almost as many hits as “Sox”. In other words, “red” has a much more even spread of collocates than “geezer”. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

These examples only scratch the surface of the wealth of information that can be dug out of these corpora. All in all then, these large online corpora provide a rich resource for translation students to explore. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Works cited: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

余華. 2010. 十個詞彙裡的中國 = China in ten words. 台北市 : 麥田出版. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Yu, Hua. 2011. China in ten words. Translated from the Chinese by Allan H. Barr. New York: Pantheon Books 2011. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

27 August 2020 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Using monolingual corpora for translation research: Proquest Historical Newspapers |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In an earlier post I wrote about my love for Early English Books Online and Eighteenth-Century Collections Online (see 16 December 2019 below), two databases that I have used extensively in my research on the history of translation between Chinese and English. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

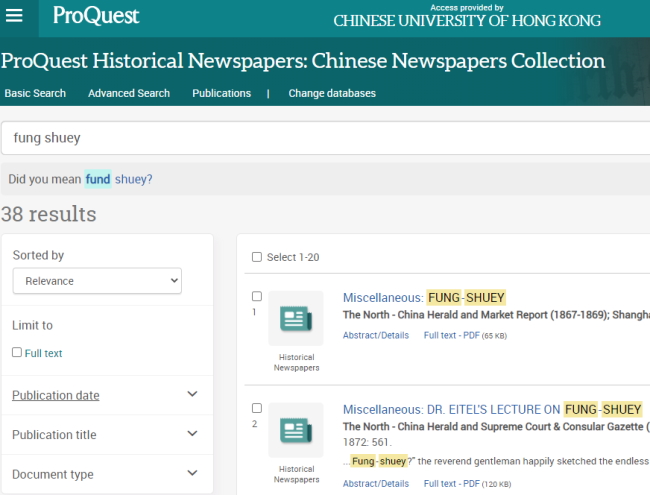

More recently I have been using another database, Proquest Historical Newspapers, to chart the development of key terms in English relating to China, especially fengshui, filial piety, and face, so I thought I would introduce briefly how I use these monolingual databases to conduct research in translation. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The main concern of the current project is how certain key terms were translated and then used in the English language, to see how the Anglo-American imagination came to grips with culturally-specific concepts from China. First, therefore, I had to make sure that I was familiar with the terms used at different periods of time to refer to these concepts. By design, I had chosen concepts that were rendered into English through a fairly narrow range of fixed terms; the main problem was identifying as many of the possible variant spellings of transliterated terms as possible. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

It is said that one of the three signs of senility in a sinologist is the invention of a new romanization system for Chinese, and indeed, there are often a bewildering array of variants. Take the term 風水. In modern hanyu pinyin, this is transliterated as fengshui. Yet the hanyu pinyin system was only invented in the 1950s, and because it was from Mainland China, scholars, government officials, and publishers in the United States resisted adopting it well into the 1980s. The history of romanization systems is complicated, including as it does the old postal spellings (Swatow is an example), the Wade system, and the later Wade-Giles system, which finally established a kind of standard among sinologists by the early twentieth century. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Translation of Chinese material has never been restricted to scholars, however, and many nonce forms for individual terms can also be found. On top of this, many terms in English derive from dialects of Chinese other than what is today standard Mandarin; in particular, Cantonese was often the basis for such translation. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Therefore, in the Proquest Historical Newspapers, I was able to identify a dozen different spellings for fengshui: feng shui, fengshui, feng shuey, feng shue, feng chui, fong shui, fong shuey, fong shue, fung shui, fungshui, fung shuy, and fung shuey. In addition, there was one translation of the term, “geomancy”, which took various forms: geomancy, geomancer, geomantic. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Each of these terms had to be searched separately; a search for fengshui (one word) and feng shui (two words, or hyphenated) returns different results. I therefore had to conduct fifteen separate searches, save each set of search results separately to an excel spreadsheet, and then combine them offline. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This was tedious work, but the results were (eventually!) rewarding. I could track statistics of how many occurrences of the different terms occurred year by year, or even month by month; not surprisingly, there was a spike in interest concerning fengshui during the Boxer Rebellion at the turn of the twentieth century, for example. The metadata also told me what publications were more likely to feature articles about fengshui (the San Francisco Chronicle in the nineteenth century; the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times in the twentieth, all three being published in cities with large Chinese communities). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A deeper dive into the data, which included accessing a selected number of the articles themselves, reveals changing patterns in collocation and changes in what fengshui meant to native English speakers. But to learn more details about what I found, I’m afraid you will have to wait for the appearance of my next monograph, tentatively entitled Conceptualizing China through Translation, expected out from Manchester University Press in late 2021 or early 2022! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

31 May 2020 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Exploring Pseudotranslation through Comparable Corpora |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

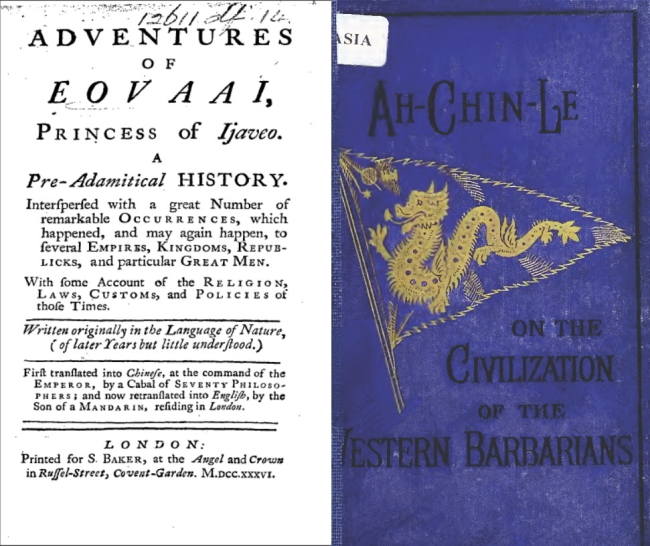

I have long been interested in the phenomenon of pseudotranslation—texts written in one language but claiming to have been translated from another. In my monograph Translating China as Cross-Identity Performance (Hawai’i 2018), I demonstrated that the history of Chinese-English translation is intimately bound up with the practice of pseudotranslation, from the eighteenth century right down to the twentieth, and in an article in my forthcoming edited volume Translation and Time (Kent State 2020), I note the relationship between translations and forgeries. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Two pseudotranslations, one from 1736 (left) and one from 1876 (right) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Beginning with Mona Baker’s work in the 1990s, there have been a host of studies that aim to demonstrate how translations have their own special characteristics, and therefore are different from original works written in a language. Simplification, explicitation, and normalization were hypothesized as translation universals and, although there has been some qualifying of those early results, the general idea that translations differ from original works, and that those differences can be tracked using corpus tools, is now well established in the field. Moreover, there have been attempts at more fine-grained analysis of how translations between specific language pairs or within certain genres function. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

To me, this raises a question: if pseudotranslations are a type of forgery that is trying to “pass” as translation, what (if any) linguistic characteristics does it mimic from translations proper? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

To answer this question, I have been directing a project to compile a three-way comparable corpora of translations from Chinese, pseudotranslations “from” Chinese, and original works written in English from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The idea is to run analysis of linguistic features in the three types of texts to determine which characteristics pseudotranslations share with real translations, and which they share with other works written originally in English. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This project has been supported by the Centre for Translation Technology over the past two years, as a number of undergraduate students have been hired on a part-time basis to digitize and proofread approximately 40 texts to produce a high-quality corpora, rather than rely on OCR scanned texts, which for this time period contain high rates of error and therefore unreliable texts. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I hope to start publishing my findings by the end of this year, so I will not say anything here about the results so far. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

More importantly for this blog is the fact that we will be making the three-way comparable corpus publicly searchable using the GoK Tool developed at the University of Manchester as part of their Genealogies of Knowledge project. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

We hope to launch this publicly by the end of the year. Stay tuned! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Works cited: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

St. André, James. Translating China as Cross-Identity Performance. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2018. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

St. André, James, ed. Translation and Time: Migration, Culture, and Identity. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, forthcoming Nov 2020. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

22 April 2020 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pursuing Digital Humanities in the age of Covid-19 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The advent of Covid-19 has meant unparalleled challenges to higher education this semester, first and foremost in terms of teaching. We all struggled to master various substitutes for classroom teaching, perhaps most commonly the use of various virtual meeting platforms, such as Zoom, Google hangout, WhatsApp, and WeChat. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Now that the semester is winding down, and our thoughts turn to the writing we all promised ourselves we would accomplish during the break from teaching, we are faced with similar challenges in terms of our research. Libraries and archives are by and large closed, and likely to remain so for at least another month. More importantly, travel restrictions mean that we cannot visit archives, museums, and other cultural institutions, carry out fieldwork, or collect data through interviews and questionnaires. The Chinese University of Hong Kong has effectively banned all but essential travel until June 15 at the earliest, and that ban will quite likely be extended if the virus continues to spread in other countries, even while here in Hong Kong the number of cases remains low. This means that even if I am able to travel for research this summer, I would have to undergo a fourteen-day quarantine period upon my return to Hong Kong. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Secondly, gatherings to share our research are also effectively on hold for the next several months. Workshops, public talks, and conferences are either cancelled or delayed, and visits to foster cooperative projects are a distant dream. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Under these circumstances, digital humanities tools have suddenly become more important than ever. Libraries, archives and repositories seem to be speeding up digitization projects, creating digital copies of an ever-wider array of materials for the use of researchers. Here at CUHK, our library has started a digitization service for materials held in the library that staff wish to consult; upon request, they will either procure an existing digital copy held elsewhere, or produce their own copy of materials that we only hold in hard copy. They have also put out announcements about a wide array of digital materials that are available, either through their subscription services or for free during the Covid-19 crisis. Without leaving my home, I can access a wider array of materials in Chinese and English than I could before the crisis began. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There are still some strange hiccups, of course. One database in particular that I have used, 中國近現代思想史全文數據庫, is only available for use on a few dedicated computers inside the library and so, during the lockdown, remains inaccessible. However, one of our librarians actually offered to search the database for me, and sent the results in a spreadsheet. Talk about service! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In terms of fostering cooperative projects and exchanging ideas, CTT is currently re-evaluating its plans for events in the coming year. Given that scholarly exchange is vital to the development of most of our research, we will be planning a series of online events, both public lectures and small-group workshops, on a series of topics related to digital humanities in translation studies. Stay tuned! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

15 March 2020 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I took a break from blogging in January for the Chinese New Year Holiday, and then February was spent dealing with the shift to online teaching and meeting various deadlines. But now I’m happy to be back in March as spring starts to arrive in Hong Kong, with the cotton trees in bloom and spring migration of birds well underway. Life goes on even in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

New project: Re-conceptualizing Chinese-English Translator Networks in the Nineteenth Century |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Thanks to generous funding from the Hong Kong Research Council, General Research Fund (project number 14604219), the Centre for Translation Technology announces the launch of a two-year project, “Re-conceptualizing Chinese-English Translator Networks in the Nineteenth Century”. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Anglo-American translators played a crucial role in intercultural communication between China and the West in the nineteenth century. This tumultuous period saw the creation and solidification of enduring stereotypes of both the Chinese to Westerners and Westerners to Chinese that are still with us; understanding who these translators were will help us better to understand where we are today in Chinese-Western interactions. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Several scholars, including myself, have already conducted in-depth research on key texts and individual translators, for example Sir George Staunton and Sir John Francis Davis. Although a few scholars have also attempted a more syncretic overview of translation activity in this period, no one has yet attempted to link details of the translators’ background and personal lives with their translation practice on a large scale. We thus lack a sense of the broader picture of why these translators chose certain texts and particular translation strategies during this crucial period in Chinese-Western interaction, which the Chinese still look back upon as the “century of humiliation.” |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This study will employ methods based on firmly established sociological analyses (Bourdieu, Latour, and Collins) and data-driven, computational social network methods to collect detailed biographical information that will then be encoded in a database. Using these to build a detailed social network map will allow us to identify hitherto unnoticed correlations between various factors including birthplace, social background, religious beliefs, profession, and societies; it will also allow us to link those trends to their choice of what to translate, how to translate it (translation strategies), and where to publish. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The study aims to yield new insights into the behavior of this crucial group of intercultural communicators, and establish links between broader historical and social trends with particular translation choices. Furthermore, it will help introduce new Digital Humanities methods into translation studies. In particular, synchronic and diachronic data visualization techniques and GIS mapping will be among those techniques employed. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The database thus created will be made publicly available. Since it is modular, it can also be expanded to include other time periods and/or other language combinations in collaboration with other scholars. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Watch this site for regular updates! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

19 December 2019 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Wonders of EBBO and ECCO |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The library here at the Chinese University of Hong Kong finally decided this year to subscribe to Eighteenth-Century Collections Online, a database that boasts it holds virtually every book published in the English language still extant published between 1701–1800. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The scanned pages have all been converted to text files through automated optical character recognition (OCR) software, and therefore are fully searchable. Despite sometimes high error rates for poorly printed works, this database provides a wealth of information for scholars in all fields of historical research, including translation studies. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The sister database to ECCO is Early English Books Online, which covers everything from the first printed book up to 1700. Although CUHK does not subscribe to it, I was able to access it during two research trips to Harvard University in July 2018 and July 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

As part of a project sponsored by the Hong Kong Research Council, GRF grant no. 14603115, I have used EEBO and ECCO to track the usage of the term “filial piety” over the course of nearly three centuries and hundreds of works, from its first appearance in Sir Philip Sydney’s Duchess of Pembroke’s Arcadia (1590), through its first direct link with China in 1669 (John Webb’s Historical Essay Endeavoring a Probability that the Language of the Empire of China is the Primitive Language), and the gradual growing association between the Chinese and the virtue of filial piety. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Searching large databases such as EEBO and ECCO did not mean that I needed to lose the granularity of historical and literary close reading, especially since filial piety is not an extremely common term. The database thus allowed me to gather both quantitative and qualitative data. Quantitatively, I was able to compare the frequency and collocations of “filial piety” with closely related terms such as filial duty, filial fear, and filial love, to name just three. This comparison demonstrated that, unlike filial fear and filial love, which collocated overwhelmingly with God as their object, filial piety was a more secular virtue, with one or both birth parents being the object of filial piety in the majority of cases. Comparison with filial duty showed that the two terms were virtually synonymous based on usage, collocation, and the fact that they were often used interchangeably in a single text. Finally, I was able to track when the term occurred in translations. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Qualitatively, I was able to identify a small number of works that actually had the term filial piety in their title, and then subjected these texts to a more rigorous close reading. This resulted in my noticing that in dramatic texts filial piety is opposed to romantic love, and that this opposition grows more marked as time goes on. I was also able to isolate texts that mentioned filial piety in China, beginning with Webb as noted above, but continuing on in several texts that demonstrate that, by the early eighteenth century, China’s reputation as a land of filial subjects was firmly entrenched in the scholarly literature. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

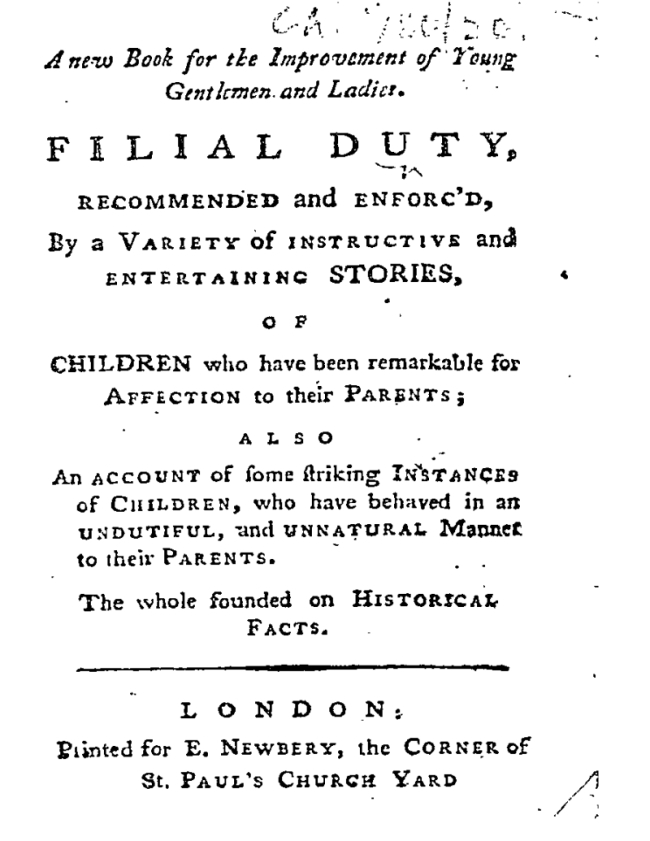

Searching databases like EEBO and ECCO often turn up serendipitous materials that you might not have dreamed existed. I found the wonderful New Book for the Improvement of Young Gentlemen and Ladies. Filial Duty, recommended and enforc’d by a Variety of instructive and entertaining Stories... (1785), which actually contains several examples of filial behavior by Chinese children, drawn from the Chinese work 孝經 (The Classic of Filial Piety) and the 二十四孝 (24 Paragons of Filial Piety). The New Book for the Improvement of Young Gentlemen and Ladies, in turn, inspired imitations and reprints in the nineteenth century, allowing me to document how knowledge of the Chinese as exemplars of filial piety spread to a wider audience outside of specialized materials. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

For those of you who are not fortunate enough to work at a university with a subscription to EEBO, the University of Michigan hosts a free version of the database that allows full bibliographic search and limited search of full-text materials (approximately 25,000 texts, or one-fifth of the 125,000). This is available here. A much smaller sample of ECCO (approximately 3500 texts out of 150,000) is also available from the University of Michigan here. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

If you want to know more about the vagaries of filial piety in English and how it metamorphoses from a Christian to a Confucian virtue, you can read my article “Consequences of the Conflation of Xiao and Filial Piety in English,” published in Translating and Interpreting Studies volume 13, no. 2 (Sep 2018), pages 296–320. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

15 November 2019 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cancellation of the international conference on Translation Studies and the Digital Humanities |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

It is with a heavy heart that today I have decided to cancel our international conference, “Translation Studies and the Digital Humanities”, originally scheduled for 9–11 December 2019. We had scheduled thirty speakers from North America, Europe, Asia and Australia over three days to address a wide variety of topics on data collection, analysis and visualization, as well as some papers on the theoretical grounding of big data. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Over the summer and into the autumn, as the protests continued, there was a conspicuous lack of activity on university campuses, where a few peaceful gatherings and marches too place; most of the gatherings were on Hong Kong Island, Kowloon, and some of the town centers in the New Territories, and most were of an ephemeral nature, lasting an afternoon or at most a day or two. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

That all changed radically on Monday (11 November), when calls for a general strike were combined by the mobilization of students on five of the major university campuses and widespread blocking of roads in addition to the disruptions to the subway service that had been ongoing. The situation quickly escalated and the campuses became war zones, with violent clashes followed by tense standoffs. There was severe damage to campus infrastructure, mainly roads and subway stations, but also some buildings. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Since the government and the protesters are not really talking to each other, there is little chance that the violence and disruption to transport and infrastructure will end any time soon, and so we felt that it was no possible to go ahead with the event in December. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Postscript: Since writing this, protesters have left the CUHK campus, but things are not expected to return to normal any time soon. Classes for the rest of semester have been cancelled and staff have been told not to enter campus until emergency crews can assess and repair the worst of the damage. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

However, although CUHK is now peaceful, other campuses continue to be battlegrounds, in particular Polytechnic University, which sits next to Hung Hom Station, an important transport hub and site of the cross-harbor tunnel, which has been closed for over a week now. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

22 October 2019 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Teaching digital humanities methods to undergraduates |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There is something wonderful about introducing students to sophisticated ways to use technology for research, instead of what they (and I!) normally use it for, i.e., facebook, snapchat, and pet memes. As part of my course “Research Methods in Translation Studies”, I devote one week to DH methods. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Last week, then, I covered first the use of “tried-and-true” corpus-based approaches, These included both parallel (source and target text aligned side by side) and comparable corpora (translated and non-translated texts in the same language), along with my more recent three-way parallel pseudo-translation corpus of English translations (and pseudo-translations) of Chinese texts. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I then gave them an example of how a parallel corpus can yield interesting insights into a text by showing them a corpus I had compiled of the 中庸 and two different English translations, one by James Legge (as “Doctrine of the Mean”) and one by Ku Hung-ming (as “The Conduct of Life. Or, the Universal Order of Confucius”). After sorting the words in the concordance program Wordsmith, I showed how the unexpectedly high frequency (121 instances) of the term “moral” in Ku’s translation highlighted the difference between his translation and Legge’s translation, which has zero instances of the term. Going back to the parallel Chinese text, it emerges that Ku frequently uses “moral” as an adjective to describe a noun to form compounds for a wide variety of Chinese terms. Here are four examples: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I tied this to Ku’s use of the word “God” as translation of 天 (compare Legge, “Heaven” or “the heavens”), his translation of 教 as “religion” (compare Legge, “instruction”), and of other words to prove that he was building up an argument (on the level of discourse) about the morality of Chinese civilization by appealing to religious sensibilities through particular vocabulary choices. (This example is adapted from St. André 2018) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Finally, I showed the students how a comparison of these collocations (law, man, being, order) for “moral” were unusual through a comparison with large English corpora held at Brigham Young University (https://www.english-corpora.org/). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The second half of the lecture was devoted to newer digital techniques, such as the use of ready-made online corpora for text mining, statistical analysis, and visualization tools. Besides the now often-cited network visualization tool Gephi, I pointed out that even simple visualization tools, such as word clouds, can be used in interesting ways. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Here I cited the work of Lorenzo Andolfatto (2018), who has demonstrated that word clouds composed of multiple translations of the same poem can yield interesting insights into how translation of the same work can change over time: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Here are two word clouds generated for one poem by Li Shangyin, “落花” (Falling Flowers), one up to 1973, the other from 1976 through 2012. The word cloud makes immediately visible the sharp difference in vocabulary choices in the two time periods. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In the tutorial session that followed the lecture, students worked in small groups, sharing ideas of how digital humanities tools could be used for their own projects (each student in the class has to write a research proposal on a question that they choose themselves). I was quite pleased at the number of students who saw the possibilities opened up by digital humanities methods, and came up with interesting ways to test a hypothesis or to visualize their data. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sources: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Andolfatto, Lorenzo. “Thick Translation through Word-Clouds; or, An Educated Form of Tasseography.” Journal of Translation Studies 2 (1): 107–26. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

St. André, James. 2018. Translating China as Cross-Identity Performance. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

23 September 2019 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Translation Technology in Times of Protest |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Living in Hong Kong, I find that acts of translation and interpretation are all around me, and that increasingly these are mediated by new and ever-changing technologies. For my first blog post, I would like to share with you my experience of watching the protests in Hong Kong through the lens of English translation on Facebook. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The protests, which were initially touched off by a proposed extradition bill but then soon grew to include other demands, have been very much a local issue and therefore a Cantonese phenomenon. Although I have learnt some Cantonese, my experience of the protests, and the government response to those protests, have been mainly dependent upon English-language materials, especially (but not limited to), postings on Facebook by both ‘friends’ (in the Facebook sense of the word, sometimes people I have never met in person), strangers, and ‘recommended’ to me by Facebook’s newsfeed algorithm. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

One recent post in particular struck me as interesting due to its multilingual format. This was the press conference held on 4 September 2019, hosted by two of the protesters, in response to Carrie Lam’s announcement that she would propose in the next session of the Legislative Council that the extradition bill be withdrawn. A link to the video on YouTube by Apple Daily, which you can watch here, was posted to Facebook multiple times. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The video is of interest in terms of translation both for what languages are represented, and how they interact. First, the entire press conference was accompanied by simultaneous sign-language interpreting. Second, the press conference was also presented in a sort of consecutive interpretation format: after one student representative (a man) had spoken for approximately 9 minutes, he ends by saying (in Cantonese) that what follows will be an English translation. The second representative (a woman) then speaks for approximately 8 minutes in English, prefacing her remarks by saying that she is going to “recap the speech in English”. This recap turned out not to be a full translation of the Cantonese speech, for at the beginning she omitted the first half-dozen sentences by the male speaker who explained the background to the press conference and how it would proceed. Crucially, at the end of the speech, she transforms the very emotional shouting of some of the key slogans into a plain, almost monotone English. At the end of the Cantonese speech, members of the crowd had chanted the slogans in response to the man’s shouting, while no one responded to her English rendition of them. Finally, during the Q&A session, which lasted longer than the Cantonese and English versions combined, there continued to be simultaneous sign language interpretation, but no English interpretation was provided for questions (and answers) in Cantonese, and no Cantonese interpretation was provided for English questions (and answers). Finally, the elephant in the room was Mandarin, a language that was totally absent from the venue. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

What are we to make of this format? First, it is interesting that the only audience whose full linguistic needs are met are the deaf. There were both local and foreign journalists present at the press conference. While we might assume that the local journalists possess sufficient English skills to understand the English Q&A, it is unlikely that the foreign journalists understood the questions of their local counterparts in Cantonese (which occupied approximately 2/3 of the entire Q&A). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The attempt, not entirely successful, to incorporate an English-speaking audience, while totally ignoring a Mandarin-speaking audience, speaks volumes for the direction of the movement and what I assume is a deliberate choice not to engage with a Mandarin-speaking audience. While presumably oriented against people living in Mainland China, it also means ignoring another audience, that in Taiwan and, to a lesser extent, Chinese communities in Southeast Asia. Yet also the lack of emotion in the English-speaker’s voice as she translated the slogans at the end indicated clearly that the English-speaking audience are conceived as bystanders or observers, not potential participants; there was no attempt to appeal to them emotionally. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Getting back to the technological side of things, the video as posted on the Apple Daily account on YouTube is only indexed in Chinese, making it impossible for an English-speaking audience to find it using an English-keywords search. It is only because I have Cantonese-speaking friends who posted and forwarded the link to me that I had access to the video. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Finally, the video shows once again the perils of being an interpreter. The two spokespeople for the movement wore hardhats and face masks to conceal their identity. The only participant whose face was visible, and therefore whose identity was revealed, was the sign language interpreter. Let us hope that the government respects the professional neutrality of her and the other sign language interpreters who appear in the growing number of videos online for all to see. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||